Beyond Work-family Balance: Advancing Gender Equity and Workplace Performance.pdf

In this entry nosotros present information and research on economic inequalities betwixt men and women. Whenever the data allows it, we also discuss how these inequalities have been changing over fourth dimension.

Equally we show, although economic gender inequalities remain common and large, they are today smaller than they used to be some decades ago.

All our charts on Economic inequality by gender

Related Our Earth in Data entries:

- Women's Employment – rising female person labor strength participation has been ane of the most remarkable economic developments of the last century. In this entry we present the key facts and drivers behind this important change.

The gender pay gap across countries and over time

The 'gender pay gap' comes up frequently in political debates, policy reports, and everyday news. But what is it? What does it tell us? Is it different from country to land? How does information technology change over fourth dimension?

Here we try to reply these questions, providing an empirical overview of the gender pay gap across countries and over fourth dimension.

The gender pay gap measures inequality just not necessarily discrimination

The gender pay gap (or the gender wage gap) is a metric that tells us the difference in pay (or wages, or income) between women and men. It'southward a measure out of inequality and captures a concept that is broader than the concept of equal pay for equal work.

Differences in pay between men and women capture differences along many possible dimensions, including worker education, experience and occupation. When the gender pay gap is calculated by comparing all male workers to all female workers – irrespective of differences along these additional dimensions – the event is the 'raw' or 'unadjusted' pay gap. On the contrary, when the gap is calculated afterward bookkeeping for underlying differences in education, experience, etc., and so the outcome is the 'adjusted' pay gap.

Discrimination in hiring practices tin exist in the absenteeism of pay gaps – for example, if women know they will exist treated unfairly and hence choose not to participate in the labor market. Similarly, it is possible to detect large pay gaps in the absences of bigotry in hiring practices – for example, if women get fair treatment merely apply for lower-paid jobs.

The implication is that observing differences in pay between men and women is neither necessary nor sufficient to testify bigotry in the workplace. Both discrimination and inequality are important. But they are non ane and the same. (Y'all can read about bigotry and 'equal pay for equal work' in our post here).

In most countries in that location is a substantial gender pay gap

Cross-land data on the gender pay gap is patchy, only the near complete source in terms of coverage is the United Nation'southward International Labour System (ILO). The visualization here presents this information. You can add together observations by clicking on the option ' Add country ' at the bottom of the nautical chart.

The estimates shown hither represent to differences betwixt average hourly earnings of men and women (expressed as a percentage of boilerplate hourly earnings of men), and cover all workers irrespective of whether they work total time or role fourth dimension.i

Equally we can see: (i) in most countries the gap is positive – women earn less than men; and (2) there are large differences in the size of this gap across countries.

(NB. By this measure the gender wage gap can exist positive or negative. If it is negative, it means that, on an hourly ground, men earn on average less than women. This happens in some countries, such as Malaysia.)

In most countries the gender pay gap has decreased in the last couple of decades

How is the gender pay gap changing over fourth dimension? To answer this question, let'southward consider this chart showing available estimates from the OECD. These estimates include OECD fellow member states, every bit well every bit some other non-member countries, and they are the longest available series of cross-country information on the gender pay gap that we are aware of.

Here we see that the gap is large in about OECD countries, but it has been going down in the concluding couple of decades. In some cases the reduction is remarkable. In the Great britain, for example, the gap went down from about 50% in 1970 to near 17% in 2016.

These estimates are not directly comparable to those from the ILO, because the pay gap is measured slightly differently hither: The OECD estimates refer to percent differences in median earnings (i.e. the gap here captures differences between men and women in the middle of the earnings distribution); and they cover but full-time employees and cocky-employed workers (i.e. the gap here excludes disparities that arise from differences in hourly wages for part-fourth dimension and full-time workers).

However, the ILO data shows similar trends for the menstruation 2000-2015.

The conclusion is that in most countries with available data, the gender pay gap has decreased in the last couple of decades.

The gender pay gap is larger for older workers

The U.s. Census Bureau defines the pay gap as the ratio between median wages – that is, they measure the gap past calculating the wages of men and women at the eye of the earnings distribution, and dividing them.

By this measure, the gender wage gap is expressed as a percent (median earnings of women as share of median earnings of men) and it is always positive. Here, values beneath 100% mean that women earn less than men, while values above 100% mean than women earn more than. Values closer to 100% reverberate a lower gap.

The next chart shows available estimates of this metric for full-time workers in the US, past age group.

First, we see that the serial trends upwards, meaning the gap has been shrinking in the concluding couple of decades. Secondly, we see that there are important differences by age.

The 2nd indicate is crucial to understand the gender pay gap: the gap is a statistic that changes during the life of a worker. In most rich countries, information technology'southward pocket-size when formal education ends and employment begins, and it increases with age. As we discuss in our analysis of the determinants, the gender pay gap tends to increment when women marry and when/if they have children.

The gender pay gap is smaller in middle-income countries – which tend to be countries with low labor force participation of women

The scatter plot hither shows available ILO estimates on the gender pay gap (vertical centrality) vs GDP per capita (on a logarithmic calibration along the horizontal axis). Every bit we tin come across there is a weak positive correlation between Gross domestic product per capita and the gender pay gap. However, the nautical chart shows that the relationship is not actually linear. Actually, middle-income countries tend to have the smallest pay gap.

The fact that heart-income countries have low gender wage gaps is, to a large extent, the result of pick of women into employment. Olivetti and Petrongolo (2008) explain it as follows: "if women who are employed tend to have relatively high‐wage characteristics, low female person employment rates may become consequent with depression gender wage gaps merely because low‐wage women would not characteristic in the observed wage distribution."two

Olivetti and Petrongolo (2008) show that this pattern holds in the information: unadjusted gender wage gaps across countries tend to be negatively correlated with gender employment gaps. That is, the gender pay gaps tend to be smaller where relatively fewer women participate in the labor force.

So, rather than reverberate greater equality, the lower wage gaps observed in some countries could indicate that only women with certain characteristics – for instance, with no hubby or children – are entering the workforce.

Representation of women in senior managerial positions

Women in management positions

The chart here plots the proportion of women in senior and heart direction positions around the world. It shows that women all over the earth are underrepresented in high-profile jobs, which tend to be better paid.

Firms with female managers

The next chart provides an alternative perspective on the same effect. Hither we evidence the share of firms that have a woman as manager. We highlight world regions past default, but you can add specific countries by using the option ' Add country '.

Every bit we can see, all over the world firms tend to be managed by men. And, globally, only almost 19% of firms take a female manager.

Firms with female managers tend to be different to firms with male person managers. For example, firms with female managers tend to likewise be firms with more female workers.

Representation of women at the superlative of the income distribution

Despite having fallen in recent decades, in that location remains a substantial pay gap between the average wages of men and women.

Just what does gender inequality look like if we focus on the very acme of the income distribution? Do we find any evidence of the so-called 'drinking glass ceiling' preventing women from reaching the peak? How did this alter over fourth dimension?

Answers to these questions are found in the piece of work of Atkinson, Casarico and Voitchovsky (2018). Using revenue enhancement records, they investigated the incomes of women and men separately across nine high-income countries. As such, they were restricted to those countries in which taxes are collected on individual basis, rather than every bit couples.three

In addition to wages they as well take into account income from investments and self-employment.

Whilst investment income tends to make up a larger share of the total income of rich individuals in general, the authors plant this to exist particularly marked in the instance of women in top income groups.

The two charts present the key figures from the written report.

One chart shows the proportion of women out of all individuals falling into the pinnacle 10%, 1% and 0.1% of the income distribution. The open circumvolve represents the share of women in the top income brackets back in 2000; the closed circumvolve shows the latest data, which is from 2013.

The other chart shows the data over fourth dimension for individual countries. You tin can explore data for other countries using the "Change state" button on the chart.

The two charts allow usa to answer the initial questions:

- Women are greatly under-represented in top income groups – they make up much less than fifty% across each of the nine countries. Within the top 1% women business relationship for around 20% and there is surprisingly little variation across countries.

- The proportion of women is lower the college y'all await upwardly the income distribution. In the top ten% upwardly to every third income-earner is a woman; in the top 0.1% simply every 5th or tenth person is a woman.

- The tendency is the same in all countries of this study: Women are now better-represented in all top income groups than they were in 2000.

- Merely improvements have generally been more limited at the very elevation. With the exception of Commonwealth of australia, we see a much smaller increase in the share of women amongst the top 0.1% than amongst the top 10%.

Overall, despite recent inroads, we continue to run into remarkably few women making it to the top of the income distribution today.

Representation of women in low-paying jobs

To a higher place nosotros show that women all over the world are underrepresented in loftier-profile jobs, which tend to exist better paid. As it turns out, in many countries women are at the same fourth dimension overrepresented in depression-paying jobs.

This is shown in the chart here, where 'depression-pay' refers to workers earning less than 2-thirds of the median (i.e. the middle) of the earnings distribution.

A share above 50% implies that women are 'overrepresented', in the sense that among those with low wages, there are more women than men.

The fact that women in rich countries are overrepresented in the bottom of the income distribution goes together with the fact that working women in these countries are overrepresented in low-paying occupations. The chart shows this for the Us.

Control over household resources

Women often have no control over their personal earned income

The chart plots cantankerous-state estimates of the share of women who are not involved in decisions about their own income. The line shows national averages, while the dots show averages for rich and poor households (i.due east. averages for women in households within the top and lesser quintiles of the corresponding national income distribution).

As nosotros tin meet, in many countries, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, a big fraction of women are not involved in household decisions virtually spending their personal earned income. And this blueprint is stronger amidst low-income households within low-income countries.

Per centum of women not involved in decisions near their ain income – Earth Development Report (2012)5

In many countries women take limited influence over important household decisions

Above we focus on whether women get to choose how their own personal income is spent. Now nosotros expect at women'southward influence over full household income.

In the next chart we plot the share of currently married women who study having a say in major household buy decisions, against national GDP per capita.

Nosotros see that in many countries, notably in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, an of import number of women have limited influence over major spending decisions.

The chart above shows that women's control over household spending tends to exist greater in richer countries. In the chart we show that this correlation also holds within countries: Women's control is greater in wealthier households. Household's wealth is shown by the quintile in the wealth distribution on the x-axis – the poorest households are in the lowest quintiles (Q1) on the left.

There are many factors at play hither, and information technology'south important to conduct in mind that this correlation partly captures the fact that richer households savor greater discretionary income across levels required to comprehend basic expenditure, while at the same time, in richer households women often have greater agency via access to broader networks also as higher personal avails and incomes.

Land ownership is more than often in the hands of men

Economical inequalities betwixt men and women manifest themselves, not only in terms of wages earned, but as well in terms of avails owned. For instance, as the chart shows, in most all depression and eye-income countries with data, men are more than likely to ain country than women.

Women's lack of control over important household assets, such every bit land, can be a critical problem in case of divorce or the hubby's death.

Closely related to the issue of state buying is the fact that in several countries women practice not have the same rights to property as men. These countries are highlighted in the map.

(This map from the World Development Written report (2012) provides a more fine-grained overview of different property regimes operating in different countries.)

Gender equal inheritance systems accept been adopted in most, but not all countries

Inheritance is one of the principal mechanisms for the accumulation of assets. In the map we provide an overview of the countries that do, and do not have gender-equal inheritance systems.

If you move the slider to 1920, you will see that while gender equal inheritance systems were very rare in the early 20th century, today they are much more mutual. And still, despite the progress achieved, in many countries, notably in North Africa and the Heart East, women and girls however have fewer inheritance rights than men and boys.

Gender differences in access to productive inputs are frequently large

To a higher place nosotros show that at that place are large gender gaps in country buying across low-income countries. Here we bear witness that there are too large gaps in terms of access to borrowed capital.

The chart shows the percentage of men and women who report borrowing whatever coin in the past 12 months to start, operate, or expand a farm or concern.

Every bit we can see, nearly everywhere, including in many rich countries, women are less likely to go borrowed capital for productive purposes.

This tin can accept big knock-on effects: In agriculture and entrepreneurship, gender differences in access to productive inputs, including state and credit, can lead to gaps in earnings via lower productivity.

Indeed, studies have institute that, when statistical gender differences in agricultural productivity exist, they oft disappear when access to and use of productive inputs are taken into account.seven

Multidimensional indices of gender inequality

Women'southward Economic Opportunity Alphabetize

The previous word focused on particularly aspects one by ane. What is the the picture on economic inequality in the aggregate?

Tracking progress across multiple dimensions of gender inequalities can be difficult, since changes across dimensions often get in different directions and take different magnitudes. Considering of this, researchers and policymakers oftentimes construct synthetic indicators that aggregate various dimensions.

The Women'southward Economical Opportunity Alphabetize (WEO) published by The Economist Intelligence Unit, is one such effort to aggregate various aspects of female economic empowerment into a single metric.

The WEO index defines women'south economical opportunity as "a set of laws, regulations, practices, customs and attitudes that let women to participate in the workforce under weather roughly equal to those of men, whether as wage-earning employees or as owners of a business." It is calculated from 29 indicators drawing on data from many sources, including the Un and the OECD.

Hither is a map showing scores on this index (college scores denote more than economic opportunities for women).

The Gender Inequality Alphabetize from the Human Development Report

The Human Development Report produced by the UN includes a composite alphabetize that captures gender inequalities across several dimensions, including economic status.

This alphabetize, called the Gender Inequality Alphabetize, measures inequalities in three dimensions: reproductive health (based on maternal mortality ratio and adolescent nascence rates); empowerment (based on proportion of parliamentary seats occupied by females and proportion of developed females aged 25 years and older with at least some secondary didactics); and economic status (based on labour marketplace participation rates of female and male populations aged 15 years and older).

The map shows scores, country by country.

Historical Gender Equality Index

The Gender Inequality Index from the Human Development Report only has data from 1995. Considering this, Sarah Carmichael, Selin Dilli and Auke Rijpma, from Utrecht Academy, produced a like blended index of gender inequality, using available information for the flow 1950-2000, in order to make aggregate comparisons over the long run.

This index covers four dimensions:

- (i) Health, measured by sex rations in life expectancy;

- (two) Socio-economical resources, measured by sexual practice ratios in average years of education and labour force participation;

- (3) Gender disparities in the household, captured by sex activity ratios in union ages; and

- (iv) Gender disparities in politics, measured past sex rations in parliamentary seats.

The results from this report are shown in the chart.

Equally nosotros tin can encounter, the second half of the 20th century saw global improvements, and the regions with the steepest increment in gender equality were Latin America and Western Europe.

Interestingly, this chart also shows that in Eastern Europe there was important progress in the period 1950-1980, but there was a reversal after the autumn of the Soviet Union.

In almost all countries, if you compare the wages of men and women you find that women tend to earn less than men. These inequalities have been narrowing across the earth. In item, over the last couple of decades nearly loftier-income countries take seen sizeable reductions in the gender pay gap.

How did these reductions come about and why do substantial gaps remain?

Before we get into the details, here is a preview of the chief points.

- An important function of the reduction in the gender pay gap in rich countries over the concluding decades is due to a historical narrowing, and often fifty-fifty reversal of the education gap betwixt men and women.

- Today, education is relatively unimportant to explicate the remaining gender pay gap in rich countries. In dissimilarity, the characteristics of the jobs that women tend to do, remain important contributing factors.

- The gender pay gap is not a direct metric of discrimination. Notwithstanding, bear witness from different contexts suggests discrimination is indeed of import to sympathise the gender pay gap. Similarly, social norms affecting the gender distribution of labor are important determinants of wage inequality.

- On the other hand, the available evidence suggests differences in psychological attributes and non-cognitive skills are at best modest factors contributing to the gender pay gap.

Differences in human upper-case letter

The adapted pay gap

Differences in earnings between men and women capture differences across many possible dimensions, including education, experience and occupation.

For instance, if nosotros consider that more than educated people tend to have higher earnings, it is natural to wait that the narrowing of the pay gap beyond the earth can be partly explained past the fact that women have been catching upward with men in terms of educational attainment, in detail years of schooling.

Indeed, since differences in educational activity partly contribute to explain differences in wages, it is common to distinguish between 'unadjusted' and 'adapted' pay differences.

When the gender pay gap is calculated past comparing all male and female workers, irrespective of differences in worker characteristics, the result is the raw or unadjusted pay gap. In dissimilarity to this, when the gap is calculated later on accounting for underlying differences in educational activity, experience, and other factors that matter for the pay gap, then the result is the adapted pay gap.

The idea of the adjusted pay gap is to brand comparisons within groups of workers with roughly like jobs, tenure and education. This allows us to tease out the extent to which different factors contribute to observed inequalities.

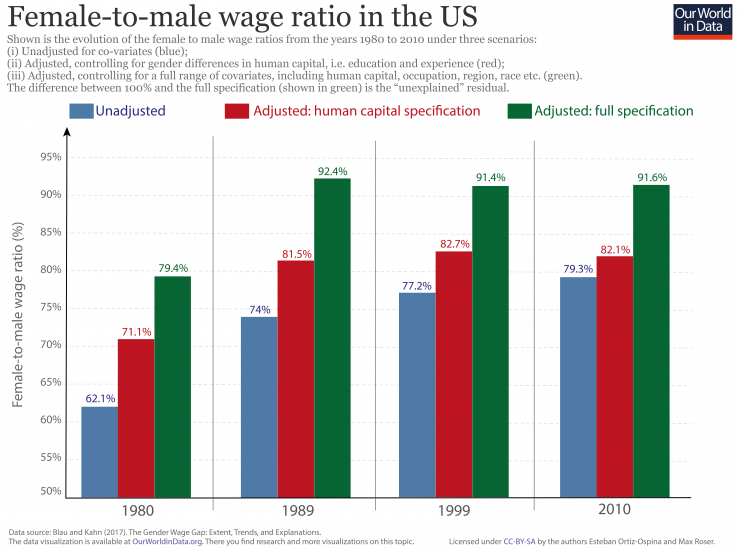

The chart here, from Blau and Kahn (2017) shows the evolution of the adjusted and unadjusted gender pay gap in the US.8

More precisely, the chart shows the evolution of female to male person wage ratios in iii dissimilar scenarios: (i) Unadjusted; (ii) Adapted, controlling for gender differences in human capital, i.east. pedagogy and experience; and (iii) Adjusted, decision-making for a full range of covariates, including pedagogy, experience, chore industry and occupation, amidst others. The divergence between 100% and the full specification (the light-green bars) is the "unexplained" residuum.nine

Several points stand out here.

- First, the unadjusted gender pay gap in the Usa shrunk over this period. This is axiomatic from the fact that the blueish bars are closer to 100% in 2010 than in 1980.

- Second, if we focus on groups of workers with roughly similar jobs, tenure and teaching, we as well come across a narrowing. The adapted gender pay gap has shrunk.

- Third, we can run across that education and experience used to assist explain a very large part of the pay gap in 1980, but this inverse substantially in the decades that followed. This 3rd point follows from the fact that the difference between the blue and red confined was much larger in 1980 than in 2010.

- And fourth, the green bars grew substantially in the 1980s, only stayed fairly constant thereafter. In other words: Nearly of the convergence in earnings occurred during the 1980s, a decade in which the "unexplained" gap shrunk substantially.

Educational activity and experience have become much less of import in explaining gender differences in wages in the The states

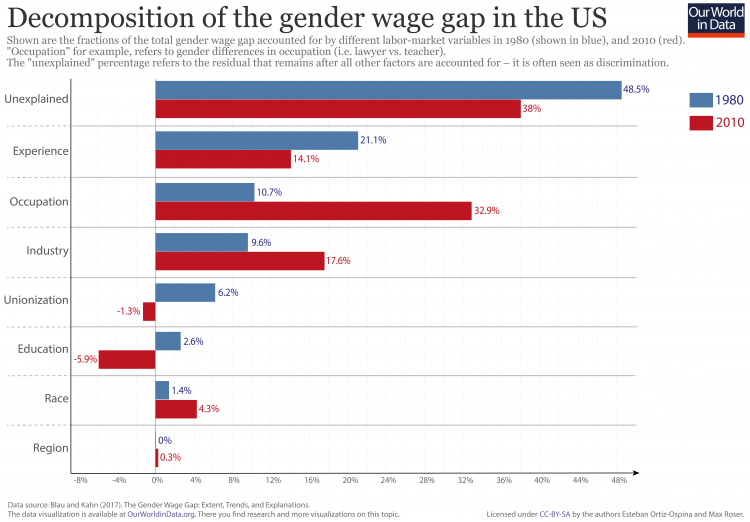

The chart here shows a breakdown of the adjusted gender pay gaps in the U.s., cistron by gene, in 1980 and 2010.

When comparing the contributing factors in 1980 and 2010, we run across that didactics and work experience have become much less important in explaining gender differences in wages over fourth dimension, while occupation and industry take become more important.x

In this chart we can also see that the 'unexplained' balance has gone downwards. This means the observable characteristics of workers and their jobs explain wage differences ameliorate today than a couple of decades agone. At beginning sight, this seems similar good news – it suggests that today there is less bigotry, in the sense that differences in earnings are today much more readily explained by differences in 'productivity' factors. But is this really the instance?

The unexplained residual may include aspects of unmeasured productivity (i.e. unobservable worker characteristics that cannot be controlled for in a regression), while the "explained" factors may themselves be vehicles of discrimination.

For example, suppose that women are indeed discriminated against, and they find information technology hard to get hired for certain jobs simply considering of their sex. This would hateful that in the adjusted specification, we would come across that occupation and industry are important contributing factors – but that is precisely because discrimination is embedded in occupational differences!

Hence, while the unexplained residual gives u.s.a. a first-social club approximation of what is going on, we need much more detailed information and analysis in social club to say something definitive about the role of discrimination in observed pay differences.

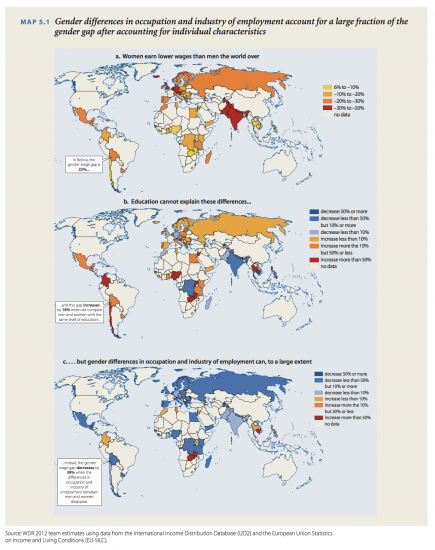

Gender pay differences effectually the earth are better explained by occupation than by education

The prepare of three maps here, taken from the World Evolution Report (2012), shows that today gender pay differences are much better explained by occupation than by pedagogy. This is consistent with the point already made above using information for the Us: as education expanded radically over the final few decades, man capital has become much less important in explaining gender differences in wages.

This web log post from Justin Sandefur at the Center for Global Development shows that teaching also fails to explain wage gaps if we include workers with aught income (i.east. if nosotros decompose the wage gap afterwards including people who are non employed).

Gender pay gap later on adjusting for education and occupation – WDR (2012)xi

Looking beyond worker characteristics

Chore flexibility

All over the earth women tend to practise more unpaid care work at dwelling house than men – and women tend to be overrepresented in depression paying jobs where they take the flexibility required to nourish to these additional responsibilities.

The most of import show regarding this link betwixt the gender pay gap and job flexibility is presented and discussed past Claudia Goldin in the commodity 'A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter', where she digs deep in the data from the U.s..12 There are some key lessons that apply both to rich and non-rich countries.

Goldin shows that when i looks at the data on occupational choice in some item, information technology becomes clear that women unduly seek jobs, including total-time jobs, that tend to be uniform with childrearing and other family responsibilities. In other words, women, more than men, are expected to take temporal flexibility in their jobs. Things like shifting hours of work and rearranging shifts to accommodate emergencies at dwelling. And these are jobs with lower earnings per hour, even when the full number of hours worked is the aforementioned.

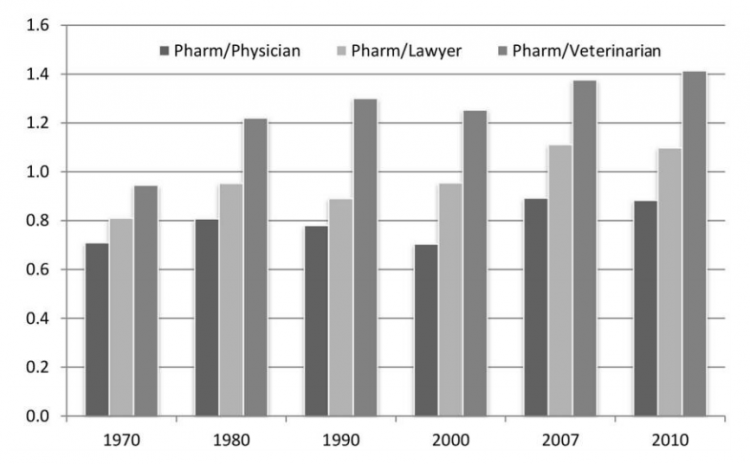

The importance of chore flexibility in this context is very conspicuously illustrated by the fact that, over the last couple of decades, women in the Usa increased their participation and remuneration in only some fields. In a recent paper, Goldin and Katz (2016) testify that chemist's became a highly remunerated female-majority profession with a pocket-size gender earnings gap in the Usa, at the same time every bit pharmacies went through substantial technological changes that made flexible jobs in the field more productive (e.g. computer systems that increased the substitutability among pharmacists).thirteen

The nautical chart hither shows how quickly female person wages increased in chemist's shop, relative to other professions, over the concluding few decades in the US.

Female median earnings of full-fourth dimension, yr-round pharmacists relative to other professions, 1970-2010, US – Goldin and Katz (2016)xiv

The maternity penalty

Closely related to job flexibility and occupational option, is the event of piece of work interruptions due to motherhood. On this front in that location is once again a cracking bargain of evidence in back up of the so-called 'motherhood punishment'.

Lundborg, Plug and Rasmussen (2017) provide show from Denmark – more specifically, Danish women who sought medical help in achieving pregnancy.xv

By tracking women'due south fertility and employment status through detailed periodic surveys, these researchers were able to establish that women who had a successful in vitro fertilization handling, ended up having lower earnings downward the line than similar women who, past risk, were unsuccessfully treated.

Lundborg, Plug and Rasmussen summarise their findings as follows: "Our main finding is that women who are successfully treated by [in vitro fertilization] earn persistently less because of having children. Nosotros explain the decline in almanac earnings by women working less when children are immature and getting paid less when children are older. Nosotros explain the decline in hourly earnings, which is often referred to equally the motherhood punishment, by women moving to lower-paid jobs that are closer to home."

The fact that the motherhood penalty is indeed virtually 'motherhood' and non 'parenthood', is supported past further evidence.

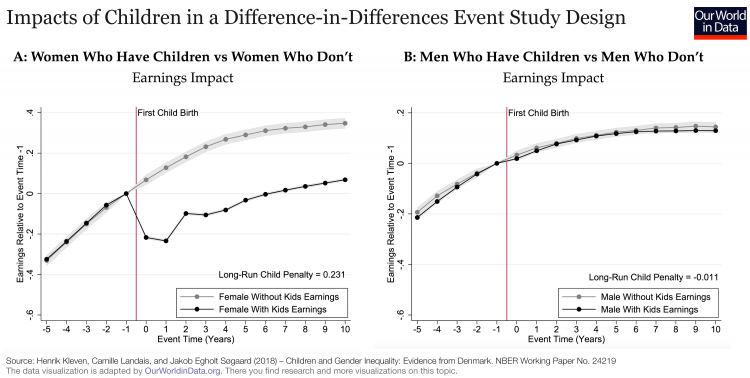

A recent report, also from Denmark, tracked men and women over the menstruation 1980-2013, and found that after the outset kid, women'south earnings sharply dropped and never fully recovered. Only this was not the instance for men with children, nor the case for women without children.

These patterns are shown in the chart here. The first console shows the trend in earnings for Danish women with and without children. The 2nd console shows the same comparison for Danish men.

Note that these 2 examples are from Denmark – a country that ranks high on gender equality measures and where in that location are legal guarantees requiring that a woman can return to the same task after taking time to give birth.

This shows that, although family-friendly policies contribute to meliorate female labor force participation and reduce the gender pay gap, they are only part of the solution. Even when in that location is generous paid leave and subsidized childcare, every bit long as mothers unduly take additional work at dwelling house after having children, inequities in pay are likely to remain.

Ability, personality and social norms

The give-and-take and so far has emphasised the importance of job characteristics and occupational choice in explaining the gender pay gap. This leads to obvious questions: What determines the systematic gender differences in occupational choice? What makes women seek job flexibility and take a disproportionate amount of unpaid care work?

Ane argument usually put forward is that, to the extent that biological differences in preferences and abilities underpin gender roles, they are the primary factors explaining the gender pay gap. In their review of the evidence, Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn (2017) show that in that location is express empirical support for this statement.sixteen

To be articulate, yep, there is evidence supporting the fact that men and women differ in some key attributes that may impact labor marketplace outcomes. For example standardised tests evidence that there are statistical gender gaps in maths scores in some countries; and experiments prove that women avoid more salary negotiations, and they oft evidence particular predisposition to accept and receive requests for tasks with low promotion potential. However, these observed differences are far from being biologically fixed – 'gendering' begins early on in life and the evidence shows that preferences and skills are highly malleable. You can influence tastes, and you lot can certainly teach people to tolerate hazard, to do maths, or to negotiate salaries.

What's more than, independently of where they come from, Blau and Kahn show that these empirically observed differences can typically only account for a modest portion of the gender pay gap.

In contrast, the evidence does propose that social norms and civilisation, which in turn bear on preferences, behaviour and incentives to foster specific skills, are key factors in understanding gender differences in labor forcefulness participation and wages. Y'all can read more about this in our blog mail dedicated to answer the question 'How well exercise innate gender differences explain the gender pay gap?'.

Discrimination and bias

Independently of the exact origin of the unequal distribution of gender roles, it is clear that our contempo and even current practices show that these roles persist with the help of institutional enforcement. Goldin (1988), for example, examines past prohibitions confronting the training and employment of married women in the Us. She touches on some well-known restrictions, such equally those against the training and employment of women as doctors and lawyers, before focusing on the lesser known simply even more impactful 'marriage bars' which arose in the late 1800s and early 1900s. These work prohibitions are of import because they applied to teaching and clerical jobs – occupations that would go the near commonly held amid married women subsequently 1950. Effectually the time the U.s.a. entered World State of war Two, it is estimated that 87% of all school boards would non hire a married woman and 70% would not retain an unmarried woman who married.17

The map here highlights that to this twenty-four hour period, explicit barriers across the world limit the extent to which women are allowed to practice the same jobs as men.18

Even so, fifty-fifty afterwards explicit barriers are lifted and legal protections put in their identify, discrimination and bias can persist in less overt ways. Goldin and Rouse (2000), for example, look at the adoption of "blind" auditions by orchestras, and show that by using a screen to muffle the identity of a candidate, impartial hiring practices increased the number of women in orchestras by 25% between 1970 and 1996.19

Many other studies take found similar testify of bias in different labor market place contexts. Biases likewise operate in other spheres of life with stiff knock-on effects on labor market outcomes. For example, at the end of World War Two but 18% of people in the Usa thought that a wife should piece of work if her married man was able to support her. This obviously circles back to our before indicate nearly social norms.20

Strategies for reducing the gender pay gap

In many countries wage inequality between men and women can be reduced by improving the teaching of women. Nevertheless, in many countries gender gaps in education have been closed and we all the same take large gender inequalities in the workforce. What else tin can be washed?

An obvious alternative is fighting discrimination. But the prove presented above shows that this is not plenty. Public policy and management changes on the firm level matter too: Family-friendly labor-marketplace policies may assist. For example, motherhood leave coverage tin contribute by raising women'southward memory over the period of childbirth, which in plough raises women's wages through the maintenance of work experience and job tenure.21

Similarly, early on instruction and childcare tin can increment the labor force participation of women — and reduce gender pay gaps — by alleviating the unpaid care work undertaken past mothers.22

Additionally, the feel of women'due south historical accelerate in specific professions (e.g. pharmacists in the U.s.a.), suggests that the gender pay gap could also be considerably reduced if firms did non have the incentive to unduly reward workers who piece of work long hours, and stock-still, not-flexible schedules.23

Changing these incentives is of course difficult because it requires reorganizing the workplace. But it is likely to have a large impact on gender inequality, particularly in countries where other measures are already in place.24

Implementing these strategies can have a positive self-reinforcing effect. For example, family-friendly labor-market policies that pb to higher labor-force zipper and salaries for women, will raise the returns to women'due south investment in education – so women in time to come generations will be more likely to invest in instruction, which volition also aid narrow gender gaps in labor marketplace outcomes down the line.25

Nevertheless, powerful as these strategies may exist, they are only part of the solution. Social norms and culture remain at the heart of family choices and the gender distribution of labor. Achieving equality in opportunities requires ensuring that nosotros change the norms and stereotypes that limit the set of choices available both to men and women. It is difficult, just the evidence shows that social norms, likewise, can be changed.

Gender pay gap

The gender pay gap (or the gender wage gap) is a metric that tells us the difference in pay (or wages, or income) between women and men. Information technology's a measure of inequality and captures a concept that is broader than the concept of equal pay for equal piece of work.

Differences in pay between men and women capture differences forth many possible dimensions, including worker education, experience and occupation. When the gender pay gap is calculated by comparing all male person workers to all female workers – irrespective of differences along these additional dimensions – the consequence is the 'raw' or unadjusted pay gap. On the opposite, when the gap is calculated after accounting for underlying differences in education, experience, etc., then the result is the adapted pay gap.

Discrimination in hiring practices can exist in the absence of pay gaps – for instance, if women know they will be treated unfairly and hence choose not to participate in the labor market place. Similarly, it is possible to discover big pay gaps in the absences of discrimination in hiring practices – for example, if women get fair handling but utilize for lower-paid jobs.

The implication is that observing differences in pay between men and women is neither necessary nor sufficient to prove bigotry in the workplace. Both bigotry and inequality are of import. But they are not ane and the aforementioned.

How is the unadjusted gender pay gap measured?

Percentage differences in average or median earnings

The gender wage gap is often measured as the departure between average earnings of men and average earnings of women expressed as a percent of average earnings of men. By this measure the gender wage gap tin be negative. This is the definition used by the ILO. (We explore the ILO data higher up.)

Comparisons of averages tin can often be misleading because averages are very sensitive to extreme information points. Hence, information technology is besides mutual to measure gender gaps past comparing earnings for the individuals at the median — or centre — of the earnings distribution. This is the definition used by the OECD. (Nosotros explore the OECD data above.)

Ratios of average or median earnings

In add-on to percent differences, it is also common to express the gender pay gap every bit a simple ratio between wages. This is the measure adopted past the Us Demography Bureau.

By this measure, the gender wage gap is expressed as a percentage (median earnings of women every bit share of median earnings of men) and it is always positive. Here, values below 100% mean that women earn less than men, while values higher up 100% mean than women earn more. Values closer to 100% reverberate a lower gap.

Data Sources

Data hubs dedicated to gender statistics

Globe Banking company – Gender Statistics

- Data Source: Multiple sources

- Clarification of available measures: Several gender indicators are included in this database. Hither are some that we encompass in this entry: Laws mandating equal remuneration for females; Firms with female peak managers; Participation of women in purchase decisions; Percentage of men and women (age 15-49) who solely own a state which is legally registered with their proper noun or cannot be sold without their signature; Ownership rights by gender; Percentage of men and women (ages xv+) who study borrowing whatever money in the past 12 months (past themselves or together with someone else) to start, operate, or expand a farm or business

- Geographical coverage: Global, by country

- Link: https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/gender-statistics

United nations – Gender Statistics

- Data Source: Multiple sources

- Description of available measures: Minimum Set of Gender Indicators, as agreed by the United nations Statistical Committee in its 44th Session in 2013.

- Geographical coverage: Global, by country

- Link: https://genderstats.un.org

OECD – Evolution Eye'due south Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI)

- Data Source: Multiple sources

- Description of available measures: This data hub covers cross-land measures of discrimination against women in social institutions (formal and informal laws, social norms, and practices) across 160 countries.

- Geographical coverage: 160 countries

- Link: www.genderindex.org

OECD – Gender data portal

- Data Source: Multiple sources

- Clarification of available measures: The OECD Gender Data Portal includes selected indicators shedding low-cal on gender inequalities in education, employment, entrepreneurship, health and development, showing how far we are from achieving gender equality and where actions is most needed. The data cover OECD member countries, also every bit partner economies including Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, and Southward Africa.

- Link: http://www.oecd.org/gender/data/

Wikigender statistics

- Data Source: Multiple sources

- Description of bachelor measures: This data hub links several external resources, including the OECD's Gender, Institutions and Development Database, as well as the OECD'due south Gender information portal

- Geographical coverage: Global past country

- Link: www.wikigender.org/statistics/

Earth Economic Forum – Global Gender Gap Study

- Data Source: Multiple sources

- Description of available measures: The World Economic Forum's information explorer compiles land rankings and profiles according to their Global Gender Gap Alphabetize scores. The index is made up of four sub-components including economic participation, education, health, and political empowerment besides equally providing a selection of contextual variables – broken downwards by gender and their combined total – relating to each of the four sub-categories. The explorer enables users to directly compare ii countries across all the indicators available.

- Geographical coverage: Global by country

- Link: http://reports.weforum.org/global-gender-gap-report-2020/dataexplorer/

Other sources referenced in this article

International Labor Organization (ILO)

- Data Source: ILO

- Description of available measures: Unadjusted gender gap in average hourly wages, Female share of low pay earners

- Time span: 1990-2016

- Geographical coverage: Global by land

- Link: http://world wide web.ilo.org/ilostat/

World Depository financial institution – Globe Evolution Indicators

- Information Source: Multiple sources

- Description of available measures: Several gender indicators are included in this database. Hither are some that nosotros cover in this entry: Laws mandating equal remuneration for females, Firms with female tiptop managers, Participation of women in purchase decisions.

- Geographical coverage: Global, by country

- Link: http://information.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators

Un Human being Development Written report

- Information Source: Multiple sources

- Description of available measures: Gender Development Alphabetize, Gender Inequality Index,

- Geographical coverage: Global, past country

- Link: http://hdr.undp.org/en/data#

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/economic-inequality-by-gender

0 Response to "Beyond Work-family Balance: Advancing Gender Equity and Workplace Performance.pdf"

Postar um comentário